Excerpt

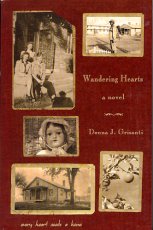

from Wandering Hearts: A Novel

Excerpt

from Wandering Hearts: A Novel

by Donna J. Grisanti

1

Raine Foster knew with certainty that she'd have to leave her home that hot, wet spring when Nanny Vi started talking to the dolls. Through tears, Raine contemplated what to do as she watched the bright pink glow of the day-ending washboard sky. The Fosters' farmhouse was falling down around Raine and her grandmother's increasingly oblivious head.

Raine looked down at her rough, chapped hands, praying that the fluffy, pink cotton candy wisps in the sky wouldn't become gray and threatening. All too frequent leaden skies poured our constant pinging rivulets that kept Raine running inside the house from bucket to rusty farm pail and then to the abandoned horse troughs she'd dragged from the rotting barn. If her prayers that the floors would stop buckling and no more leaks would spring from the Swiss cheese-like roof over their heads weren't answered, she feared the second floor of the house would fall down and kill them in their beds.

People said Raine should leave the place and get started on her own life, even in this Depression time. Back tax vultures were circling the land in this backwater place, they said. The assessor's rolltop desk was littered with tax notices, and no one in this generation had the money to pay anything at all to save long-held family properties. The landscape was riddled with broken dreams and lost fortunes big and small, like theirs, and in most folks' estimation, the only way out was for Raine to leave or to marry. She had no money to leave, at least not enough to buy a nice seat on the train that stopped at Clinforks. So "starve here or marry" was the solemn advice of the old men in the few creaking rockers and barrel stools on the sagging front porch of Vitman's general store, post office, and cotton-gin office.

Almost halfway into 1941 in Bridgeville, the old men in town had nothing better to do than come each weekday and Saturday morning in their clean but raggedy clothes to rock on the store porch in creaking comfort. They sat their days away, keeping the clerk, postmaster, and fix-it man company while watching people try to stretch their pay for supplies. The hard work of seeing folks trying to scrape a few pennies together to keep meals on the table tired them out. Things had been bad in Bridgeville for as long as anyone could remember. The Foster place, Raine's home, seemed next on the long list of failures that didn't show any sign of ending, the wrinkle-faced elders would say as they chewed on the ends of their empty pipes.

The porch elders were in a cantankerous mood, not being able to taste, or at least smell, the ripe fragrance of burning tobacco. It made the old gentlemen a bit irritable to be denied the luxury of pipe or chewing tobacco because there was no more money, either in their pockets or their family's coffers. Their fading hearing longed for the deep-pocket snap of the round tins holding the golden or tarry shaved leaves. Sometimes they would lift their worn-out bodies from the porch rockers and circle the front of the cash register, praying that the air currents would bring a few fragrant whiffs from the glass sanctuary where Vitman kept the tobacco products lined up in gleaming tins and pouches, so near and yet so far from their lips, mouths, and pipe bowls.

"We might be in luck, boys," Earll Miller said as he moved the end of his empty pipe from one moist corner of his mouth to the other. "Hear from Vestell Wright that Mr. Emil Vitman's going to the Fosters' place tomorrow." He held off a second to make sure everyone was listening to his juicy piece of gossip concerning the tall, square-jawed owner of most of the businesses in their small town. If Earll had it right, he would be the purveyor of something to keep people talking for weeks far beyond the buckling boards of the general store's porch.

One thing everybody already knew was that Emil Vitman was a mostly sour, spoiled-by-riches man past thirty. Earll sat forward in the best of the ancient rockers, made eye contact with each of the other four old men sitting with him, and said in a low voice, "Looks like there's something important going on." He knew he had them all interested, as each of his compatriots sat up and strained to hear every word. Earll shook his head solemnly, imitating the style of the circuit preacher who came every fourth week to the church down the dirt path called Pine Road.

Earll had gotten this important information from Vestell Wright, the plump widow who had been the Vitman cook and housekeeper since her husband died of rheumatism five years earlier. "Seems young Vitman's going to take himself a wife."

Earll seemed pleased with the bug-eyed reception his news engendered in his front porch cronies. He was especially satisfied with Pete Fisher's reaction. When old Pete reached for his knees with both hands, stretched his neck as if he'd stopped breathing for a few seconds, and then let all the air out in his wheezy lungs, Earll knew the news he was spreading was having its desired effect.

"Yessir, Vitman and Raine Foster," Earll said with authority, as if he could afford to buy the local paper and was reading from the four-page weekly Bridgeville Gazette. "Perhaps we'll have a good meal and a better smoke when we attend the nuptials." The men's mouths watered at the thought of the taste of cigars and good-grade tobacco curling from their pipes.

Brady Fell, the Vitmans' fix-it man, wasn't so pleased by the news. Eavesdropping might be unmannerly, but it was necessary in this case, he thought. If his seventeen years as a Vitman employee were any indication, being Vitman's wife might save Raine Foster from starving, but there were other things to consider, like the cruelties of his wealthy and powerful boss, which Brady and everyone else in town had witnessed.

Brady shook his head in disgust. He needed this menial job and needed to mind his own business. It was the only thing that had kept him, his wife, and their three children going since the accident at the Vitman cotton mill had cost him six broken ribs, a bum leg, and the loss of the family farm during his long convalescence. The farm deed belonged to Vitman now, and Brady and his family were allowed to stay there on that mean man's whim. If he butted his nose into this situation about Vitman and Raine Foster, he and his family could be out on the dirt road without a house or a job before nightfall.

Although Brady was anxiously waiting for his oldest, Imogene, to get herself a husband and give him one less mouth to feed, his conscience got hold of him. Even if it meant another ten years of watering down the gravy and eating more week-old biscuits saved from the Vitman store trash, he'd rather risk homelessness then have Raine Foster marry his boss. Trying to make sense of Emil Vitman's thundering moods, which changed more frequently than the hairstyle posters in the window of Miss Clover's Wash and Curl Hair Salon down the street, would likely kill any woman. Not only that, but Vitman was also known for adding physical violence to the quicksilver mix. Vitman saved himself from the consequences of his irrational deeds by using his power and money to tidy up every mess.

Brady thought things over again. He was bone tired this Wednesday afternoon and hadn't wanted to do one more thing than his work chores. This information changed his mind. He'd have to be late for supper and warn Miss Raine that the devil, in the form of Mr. Vitman, was coming to call.

To keep them going, Raine worked in the vegetable and flower patch and sold the flowers and produce at her makeshift roadside stand. To quiet Nanny Vi while she worked, Raine set the remaining dolls from the dwindling family collection on small wooden chairs in a tea party semicircle around her now frail, wispy-haired grandmother.

No matter how hard Raine tried to prevent it, when she combed her grandmother's once thick brown hair, the now fine, downy edges of the greatly thinned mass laced with steel gray strands would start to slip from the tight bun at Nanny Vi's neck. Raine wondered if her own thick auburn tresses, which were curly at the root and wavy at the long ends, would look the same if she lived as long as Nanny Vi. She now fixed her hair in the same tight knot at the back of her own head because there was no time to mess with it. Lots of things were gone, like real tea parties and loose tresses catching in the sweat of her face as she worked in the vegetable and flower garden.

Her grandmother hadn't been out of the house in several weeks. On their last trip to Bridgeville for flour and lard, Nanny Vi had started talking to dead people again as if they were still alive. Raine decided she couldn't allow her grandmother to be exposed to the sad, questioning eyes that remembered a different Vidalia Foster, the strong horsewoman and doll maker who was now a frail woman talking nonsense. Raine had to lock the outside doors and push the furniture to block interior access to the dangerous, uninhabitable second floor of the house when Nanny Vi was in a wandering mood.

There was also a debt to pay Brady. When she saw him on the last trip, Brady had told her, "I gave your grandmother a three-cent stamp. Paid for it myself." He'd watched Nanny Vi place a packet of papers in the mailbox at the general store while Raine was putting the parcels in the mule cart. Raine still hadn't figured out how Nanny Vi had gotten to the notepaper or managed to hide the envelope. She'd have to apologize to the postmaster if he discovered her grandmother's gibberish in with the rest of the mail. The last time she'd been in town, he was in bed with a mustard plaster and hot lemonade and whiskey, fighting a cold well away from the post office. The apology to the postmaster could wait, but when she went to general store at the end of the week, she was going to give Brady the three pennies she'd scraped together. Mrs. Simpson would be paying her tomorrow.

The wasted money wasn't the only thing. Neither Raine nor Nanny Vi had worked in the doll making business for more than a year. There was neither a market for the expensive porcelain dolls, nor the money to buy the intricate parts for the fragile beauties, their ornate clothes, or the expensive rocking eyes that opened when the dolls were upright and closed when the dolls slumbered in their bed. There was nothing else left to sell at the Foster place to buy the doll parts. All the money they had went for food and necessities. The old mule was the only stock left in the barns, as well as the only thing they were still able to feed besides themselves.

Nanny Vi and Raine had tried to keep the doll making tradition going with cloth dolls and even corn husk dolls. They sold only a few because people could make them from their own scraps and fields. Then Nanny Vi got sick. The only dolls they made now were for people with no money who needed dolls for gifts and holidays. Raine kept her hope and talent alive by collecting the best of the scratchy corn husks and the faded cloth pieces that were too small for her neighbors' quilts.

Raine wondered how long they'd last this way. As if the house falling down around them weren't enough, a few weeks earlier Nanny Vi had started chatting with two invisible people. The old woman called to them restively day and night. "Where are you, Ben?" she'd call. "Are you going to come in here soon, Charlotte?" Raine didn't want to do it, thinking that giving in to her grandmother's demands weakened the woman's faltering grasp on reality, but finally she fashioned two more dolls to represent these unknown people. No matter how many times Raine tried to ask her grandmother about them, Nanny Vi wouldn't say that Raine had never known a Charlotte and Ben.

The young woman had learned a hard lesson in keeping the peace. The last time Raine had tried to tell her grandmother that Raine's parents, as well as Nanny Vi's husband and parents, were all buried on the small sloped hill at the edge of their property, Nanny Vi had left the house. While Raine was working in the vegetable garden, Nanny Vi wandered two farms over calling for her husband, who she thought had gone over to the Nelson farm to sharpen his garden tools on the sharpening stone that Raine and everyone else in the neighborhood knew had been sold two years ago in the property sale after Ella Nelson died. Mr. Nelson had died five years earlier, and nothing was going to get sharpened that day except the gossips' tongues as they passed along this sad tale about Nanny Vi and her out-of-her-head wanderings.

Raine never again wanted to feel that pressure in her chest or cry out in terror as she had after her grandmother's irrational flight from the house. So she kept her peace and her information to herself while hushing her grandmother and working on creating Charlotte and Ben dolls from wood and cloth. Then after they'd had their late lunch and a trip to the outhouse, she dutifully placed them in the doll circle around her grandmother's rickety upholstered chair. Raine lifted her eyebrows in frustration, but said nothing.

Suddenly Raine heard a noise. There was someone at the vegetable stand. Bridey Taylor had told her she would come by to get cabbages after she'd dropped off the laundry at Judge Marshall's house.

After she paid the nickel for several large heads, Bridey rubbed her chafed hands. "I wish the Judge didn't want so much starch in his shirts," she said. "I can't understand how the stiffness can give me such a rash and the Judge's neck still stay as smooth as baby's bottom."

Raine gave her a dollop of udder cream on a piece of brown paper tied in a rag.

"Thank you," Bridey said. "I need to get home to my laundry, but you know I wish I'd had the time to listen to the old men at the general store. Might've had some news to share." She looked in her bag. "They seemed mighty interested in some tale or another." She recalled the men sitting around the general store when she went to get more starch powder. "Earll Miller and his boys all seemed like cats that had swallowed canaries, sure enough. If I wasn't so tired, I'd have asked them what was up. Even looked at my skirt hem to see if my slip was showing, they looked so beady-eyed."

Concentrating on her next chore, Raine began to empty and carry the last of the ragtag collection of buckets, pails, and cans to her garden of water collected from the holes in the roof, which sat under the partial protection of a stately oak. The tree took the brunt of the hot sun and showers, protecting the fragile garden stems. Raine had taken a chance planting a few rows of corn earlier than usual, and the stalks had withstood the early heat and all the rain. She hoped these would bring her some extra money as well.

As Raine was considering which spring flowers would make a nice bouquet for Mrs. Simpson's dinner table, she heard a familiar voice whisper from the bushes, "Miss Raine, I got to talk to you."

"Brady? What you doing in the bushes?" Raine asked in an amused tone.

"Don't say my name again, and keep doing what you're doing. This is important!" Brady replied in a harsh whisper. Raine was confused, but she tried not to be stiff and unnatural as she concentrated on the flowers.

"I'm taking some flowers to the Simpsons' tomorrow," was all she could think to say.

"I can't stay long, but there's some bad news." Brady gulped. He didn't know how to say it, but knowing that Miss Raine was his friend and that she needed to know, he kept going anyway. "Earll Miller said his lady friend, Vestell Wright, told him Mr. Vitman is coming over to ask you to be his bride."

Raine stood up straight like someone had struck her full force in the back. The flowers she looked at became hazy and then came back into focus. She grabbed her waist with her hands as if she were protecting herself from a sudden icy cold. "You sure?"

"Miss Raine, you know me better. I wouldn't tell you no lie or risk being fired from my job for no foolishness," Brady replied, still fidgeting in his bent-leg position, making sure he had his one good foot on the ground in case anyone had followed him from the general store. Mr. Vitman had plenty of spies down at the cotton gin, paid to do anything. A running start was all he asked if he'd been followed.

Raine swallowed and, not having enough breath as her heart pounded in her throat, whispered, "You go home now, Brady, and be careful. I thank you, and I'll take it from here." Her hands reached for the flower stems she was looking at and caressed the thin, green shafts. It was as if she'd seen her own death certificate signed. After a few short words, she now knew she'd have to leave and never return. She couldn't turn Emil Vitman down and live anywhere near Bridgeville. Vitman would poison everything if he thought she had crossed him. She'd need to exile herself from everything she knew and loved in order to save her own life because she knew he'd either have her or see her dead.

What am I going to do and how am I going to do it? she wondered as iciness crept through her. Emil Vitman had been drinking, carousing, and fighting his way around the area for years now. Why should she be the target of his matrimonial plans? Ever since his daddy had died in the same flu epidemic that killed her parents, there was no one to bridle that erratic man or his goons, who acted first and then used Vitman's money to get themselves out of trouble later. He was as mean as a snake and twice as dangerous, because in addition to money, he had the added currency of family connections of many generations' standing. Several people had died in the last few years because they had come too close to Vitman's temper. Who could say anything when the evildoer owned most of the town and paid off the people who knew things? Raine needed to plan -- and fast. Thank goodness Brady's warning had bought her some time, she thought as she closed her eyes and took a deep breath.

When Raine tried not to think about Brady's news, her mind would snatch it back to conscious thought at the sheer enormity and horror of the prospect. Emil Vitman was not a patient man, so she'd have to play for time. There was Nanny Vi to think of; she was gone from her right mind more often now. Perhaps this would give Raine some leeway.

For all his hell-raising, Emil was a stickler for propriety in other people. A raving grandmother-in-law in the Vitman mansion wasn't something Emil would want, and Raine wasn't going to send her grandmother to the state sanitarium. She could play on people's sentiments about a granddaughter wanting to keep her only living relative near her, even if people did think Nanny Vi was crazy now. Raine wasn't sure. In her estimation, there seemed to be room for only one crazy person in the Vitman place, and that was Emil himself.

Emil Vitman was the product of the lovely, too-pampered daughter of a rum merchant who died a few days after his child's birth and the watered-down bloodline of formerly hardworking, respectable stock on his father's side. Fortunately for him, respect died hard, and connections could be bought in these lean times. So Emil successfully greased palms and mended fences after his binge blackouts and rages. As his neighbors, staff, and store patrons attested, he became progressively more moody as his sober hours shrank.

As word spread about the possible wedding, some observers were sarcastic enough to wonder in private if his increasingly surly moods might match the less frequent lucid moments of his future fiancée's grandmother. Although all the gossips in town observed that Emil's good looks were fading under the constant barrage of liquor, they made their comments outside of his earshot to avoid becoming the focus of his erratic, vengeful temper. They never knew when they might need a favor from the puffy-eyed, preening Vitman.

When Vitman made up his mind, he could not be dissuaded. He was convinced that Raine Foster was the answer to his problems. Raine, his soon to be ever-so-grateful wife, would take care of the store and his petty problems. Acting on his orders, his muscled assistants from the cotton gin could concentrate on handling more important things. He'd be free to consider weightier matters and give orders to all of them from the comfort of the leather chair in his library, with the cut-glass decanter of bourbon at his side.

Although nearly penniless, Raine had a fine pedigree, which certainly counted in his community. She could smooth things over on the church and social fronts. He'd keep the books of his businesses, set the credit rules, and let her run the rest -- just as long as she didn't ask to fix up that wreck of a homestead she and her grandmother were living in. Their ramshackle home had to be filled with all kinds of must and contagion, proof that Raine came from hardy stock and would make an excellent broodmare for his many forthcoming children. They would be her responsibility, too, he thought as he considered the delights of home, hearth, and business. Perhaps he could even manage some discreet dalliances on the side.

He had to plan carefully. Just to be safe from the decaying pile of lumber Raine called home, he would call her out on the lawn to talk about his plans and their upcoming marriage. With her hand-to-mouth existence, she couldn't last much longer. If his spies had it right, there were only a few dolls left from her great-great-grand-mother's collection of French dolls. If Raine stretched the money, it would last a year at most. Then there would be nothing else except her vegetables and flowers to sustain her and her grandmother.

Emil thought a minute. He could send Sweeney from the cotton gin over to steal the dolls and hasten the process. He tucked the possibility away as a last resort in order to get his way. Though he relished winning by any means necessary, he still considered matrimony a fine, honorable thing. He wouldn't use any more force than necessary, unless Miss Raine gave him a reason to reconsider his tactics.

Emil looked in the mirror at his relatively handsome face, missing the signals of his increasing liquor consumption -- reddening facial skin and the beginning of tiny broken blood vessels around his nose. He turned his head and admired the legendary Vitman cocoa brown hair, which kept its color well for all the men in the family until near the time they entered the hereafter.

There had been a few other changes in Emil. At thirty-seven, he had taken to wearing vests even in the warmest weather because the material hid his burgeoning waist. His blue eyes were a bit bloodshot, but there was always some ragweed around, wasn't there? He turned a bit to consider his profile. With his long legs, he still rode a horse well when he thought to take to horseback. But he preferred the sedan Brady Fell washed and waxed every Wednesday morning, or whenever Emil wanted to remove any grime from Bridgeville's puddles and ruts. Brady could restock shelves or take inventory later. Emil enjoyed seeing his reflection in the clean coal-black finish of his Packard.

Should that be the way he greeted his ladylove? Emil wondered. No, he thought, as he considered the classics his tutor had read to him those long ago years when he couldn't be bothered to pick them up himself. Even then, he had been misunderstood at the community school. His father had hired a tutor for him, but the thin, spindly-legged man -- named Harris, if Emil remembered correctly -- ran away one night with some farmer's daughter from the other side of town. In the grand style of romantic literature, Emil thought, he should ride over to the Foster house on his horse, Renegade, to impress Miss Raine. Women liked that kind of romantic drivel.

When Raine Foster said yes, his ride over on horseback was all the romance she was going to get besides her wedding day. So he'd go to the trouble of having his stable hands wash and curry Renegade and then make sure Mrs. Wright got the horse smell out of his clothes after he got back from the Foster place.

Emil fished into the breast pocket of his gold satin vest, feeling for the ring taken from his Aunt Clara's body after she had died seven years ago. If memory served Emil correctly, her hand and Miss Raine's were similar, so there was no use in wasting good money. After all, there was still the cost of the wedding bands. Besides, didn't women like sentiment? He could tell Raine some cock-and-bull story and save himself the cost of a new engagement ring. She wouldn't be wearing it long anyway after she started working in the store and taking care of their children. It would just come back to him and sit in his jewelry box. She'd get a plain gold band to mark her as his wife.

After a heaping breakfast of country ham and eggs with Mrs. Wright's biscuits, followed by a light bourbon and water to brace himself, Emil Vitman set out for the Foster farm on Renegade at a light trot. Although he loved the thought of flying through the air on a galloping horse, he saw no reason today to jump fences and get the horse or himself sweaty. Emil patted his Aunt Clara's ring in his vest pocket. As he reined in his fine black horse about fifty yards from Raine's front door, a light breeze rippled through the tall shading oak trees at the front of the once-proud Foster home.

Copyright © 2006 Phoenix Publishing Corp.