Excerpt

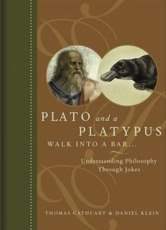

from Plato and a Platypus Walk Into a Bar . . .

Excerpt

from Plato and a Platypus Walk Into a Bar . . .

by Thomas Cathcart and Daniel Klein

During the Middle Ages this question boiled down to whether divine revelation trumps reason as a source of human knowledge or vice versa.

Hanging by a root has a tendency to tip the scales toward reason.

In the seventeenth century, René Descartes opted for reason over a divine source of knowledge. This came to be known as putting Descartes before the source.

Descartes probably wishes he'd never said, "Cogito ergo sum" ("I think, therefore I am"), because it's all anybody ever remembers about him -- that and the fact that he said it while sitting inside a bread oven. As if that weren't bad enough, his "cogito" is constantly misinterpreted to mean that Descartes believed thinking is an essential characteristic of being human. Well, actually, he did believe that, but that has nothing whatsoever to do with cogito ergo sum. Descartes arrived at the cogito through an experiment in radical doubt to discover if there was anything he could be certain of; that is, anything that he could not doubt away. He started out by doubting the existence of the external world. That was easy enough. Perhaps he was dreaming or hallucinating. Then he tried doubting his own existence. But doubt as he would, he kept coming up against the fact that there was a doubter. Must be himself! He could not doubt his own doubting. He could have saved himself a lot of misinterpretation if only he had said, "Dubito ergo sum."

Every American criminal-trial judge asks the jury to mimic Descartes's process of looking for certainty by testing the assertion of the defendant's guilt against a standard almost as high as Descartes's. The question for the jury is not identical to Descartes's; the judge does not ask whether the defendant's guilt is open to any doubt, but only whether it is open to reasonable doubt. But even this lower standard demands that the jury carry out a similar- -- and nearly as radical -- mental experiment as Descartes did.

He looked toward the courtroom door. The jurors, stunned, all looked eagerly. A minute passed. Nothing happened. Finally the lawyer said, "Actually, I made up the business about the dead man walking in. But you all looked at the door with anticipation. I therefore put it to you that there is reasonable doubt in this case as to whether anyone was killed, and I must insist that you return a verdict of 'not guilty.'"

The jury retired to deliberate. A few minutes later, they returned and pronounced a verdict of "guilty."

"But how could you do that!" bellowed the lawyer. "You must have had some doubt. I saw all of you stare at the door."

Copyright © 2007 Thomas Cathcart and Daniel Klein