Excerpt

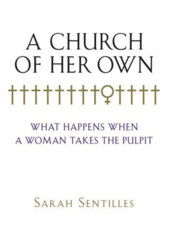

from A Church of Her Own: What Happens When a Woman Takes the Pulpit

Excerpt

from A Church of Her Own: What Happens When a Woman Takes the Pulpit

by Sarah Sentilles

Chapter One

The Call

I once heard the rector of my church in Pasadena quote Frederick

Buechner’s definition of vocation in a sermon. Vocation, Buechner

says, is the place where the world’s greatest need and a

person’s greatest joy meet. Although selfless struggle is

seductive, doing the work the world needs -- fighting poverty, racism,

sexism, imperialism, environmental destruction -- is only half of the

equation. The work that is yours must also bring you joy.

The word "vocation" comes from the Latin verb vocare, which means "to

call." Vocation as "calling" has dominated how it is understood in

religious contexts. For many who are considering being ordained, the

idea of call is something literal: The voice of God speaks, directing

the listener to a life of ministry. For others, the idea of call is

figurative: It might come as a feeling, a kind of knowing, a crazy idea

that won’t leave, a sense that this is the work they are meant to

do in the world. Sometimes call is understood as the pattern that

emerges in a string of events. Other times the voices calling belong to

friends and family or to the words on the pages of a book.

The Bible is filled with stories about people who hear the voice of God

calling them to a certain kind of work. The plot of most biblical call

stories is fairly standard: Someone hears the voice of God; rejects the

idea that he or she is the right person for the job by listing all the

ways she or he is not up to the task; tries to avoid God’s call

by running away (remember Jonah?); and, eventually, answers the call,

doing what God demands that he or she do. Most often, God calls people

by saying their names. "Abraham," God says, and Abraham -- or Amos or

Isaiah or Sarah -- answers, "Here I am." The Hebrew word for "Here I

am," hineini, can be translated as "ready." God’s prophets answer

God’s call by saying ready, even before they know what they will

be asked to do.

For many Christian denominations, believing that you have been called

is a central requirement for getting ordained. Whether you believe your

call came as the voice of God or as a feeling inside of you, you have

to be able to tell your story to others in a way that reveals you have

indeed been called to be a minister. The task of the budding minister

is to persuade a committee or a priest or a pastor not only that she

wants to be ordained but that God intends for her to be ordained.

Call sets ministry apart from all other vocations, constructs being a

priest or a pastor as radically different than being a plumber or a

teacher or a lawyer. I believe that we are all called to something,

that Buechner’s idea of vocation is open to everyone, that we all

ought to have the freedom to find that place where our deepest joy and

the world’s greatest need meet. But doctors and architects

don’t have to prove they have found that place. Ministers do.

Even though most of the women I interviewed questioned the category

"call," it remained central to the language they used to tell me when

they knew they wanted to be ordained. And this language served them

more than it got in their way. Claiming your call is an empowering

thing to do when other people are telling you that you cannot be a

minister because you are gay, or female, or Black, or too political, or

too young, or too whatever is outside the dominant version of

"minister." Women denied access to ordination -- either by their

denominations or by individual people in authority -- have used their

sense of call to sustain them in the struggle. The knowledge that they

have been called by God gives them strength to resist oppression,

furnishes them with the clarity needed to fight for their vocation and

for their rights.

The central idea of Protestantism -- that each human being has access

to God, unmediated by an institutional hierarchy -- has worked in

women’s favor. Claims of direct communication grant women

authority even when their denominations refuse to. Women have

understood themselves as ordained by God, if not by the institutional

church, and this knowledge has empowered them. At the same time,

women’s assertions have exposed a fundamental inconsistency in

Protestantism: the theological conviction that all human beings are

equal before God and the simultaneous belief that some human beings

(men, Whites, straight, propertied) are better than others (women,

people of color, homosexuals, poor). The professed equality of all

human beings has not translated into actual equality.

Many of the women I interviewed knew from a very early age that they

wanted to be ministers. Although we sometimes like to believe that they

don’t, and even hope that they aren’t, children pay

attention in church and in Sunday school. Most of the women I

interviewed attended church as children. They loved church. Some went

to church alone, without their parents or siblings. Some worried that

when something bad happened to someone they loved it was because they

didn’t pray hard enough or long enough or because they fell

asleep before they finished their prayers. Some held secret communion

services in their bedrooms and tree houses, pressing Wonder bread flat

between their hands and drinking juice. Some cried, not because they

didn’t get asked to a dance but because their churches

wouldn’t let girls be acolytes. When they were teenagers, some

went to church on Wednesday nights and Sunday mornings. They listened

to sermons, fell in love with liturgy, whispered memorized prayers in

their rooms, asked important questions a few adults were brave enough

to admit they didn’t know the answers to. They craved ritual.

They sensed hypocrisy, understood the difference between what happened

on Sunday mornings and what happened during the rest of the week, or

even what happened in the parking lot right after church. They noticed

when they were asked to participate, when they were given

responsibility, when someone cared that they were there.

Although many women knew from a young age that they wanted to be

ministers, most did not know any female ministers, making it hard for

them to imagine themselves as ministers. Because either they did not

know any female ministers or they did not know women could be ministers

at all, their feeling that they wanted to be ordained sometimes made

them feel crazy.

Most of the women I interviewed remember the first time they saw an

ordained woman and how this vision opened up their sense of vocation.

Jamie Washam, an American Baptist pastor in Milwaukee, grew up Southern

Baptist in Texas and didn’t see any female pastors. The women she

did see in church, women who were shut out of most leadership positions

even though they practically ran the church, didn’t look like

her. "Zipper Bibles, elastic pants, big ol’ white sneakers, what

would jesus do bracelets," she said. "I mean, that’s not what I

look like."

It might at first seem shallow, the idea that somehow you need to see

someone who looks like you, even dresses like you, to be able to

imagine yourself doing a certain job, but seeing a minister who looked

like them or talked like them or had theology like them signaled to

these women that there was a place for them in the church. It was a

kind of welcome, and it was only when they felt this welcome that they

realized how shut out they had been feeling. When you belong to a group

that religions hate and ostracize -- or just ignore -- you have to be

able to imagine what you have not yet seen or heard. This is holy work.

And it is work these women did. Called to be something they had never

seen, something their families, their denominations, their churches,

and their congregations had never seen, they chose ordained ministry.

For every single one of the women I interviewed, it was

Buechner’s definition that shaped her vocation. I have seen many

of them at work. Watching them celebrate weddings, preach sermons,

share communion, march in protests, lead congregations in prayer, speak

out against injustice, I had no doubt in my mind that they were meant

to be ministers. They seemed to glow, as if all the molecules in their

bodies had lined up to say yes, this is what I was made to do. This is

what brings me alive. This is where the world’s greatest need and

my deepest joy meet.

Copyright © 2008 by Sarah Sentilles