Excerpt

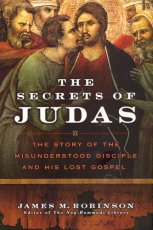

from The Secrets of Judas: The Story of the Misunderstood Disciple and His Lost Gospel

Excerpt

from The Secrets of Judas: The Story of the Misunderstood Disciple and His Lost Gospel

by James M. Robinson

Judas Iscariot is, if not the most famous, then surely the most infamous, of the inner circle of Jesus' disciples. He was one of the Twelve Apostles who stuck with Jesus through thick and thin to the bitter end, until the night of the Last Supper when he led the authorities to arrest Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. Was Judas just fulfilling prophecy, implementing the plan of God for Jesus to die for our sins, doing what Jesus told him to do? Why else would he identify him with a kiss, all for a measly sum of thirty pieces of silver? What do the Gospels inside the New

Testament -- and then what does The Gospel of Judas outside the New

Testament -- tell us about all this? . . .

A “Gospel”? By “Judas”?

The Gospel of Judas was composed after the canonical Gospels were written, at about the same time as the Nag Hammadi Gospels were written. No doubt, like them, The Gospel of Judas made use of the title Gospel to accredit itself over against the canonical Gospels that had popularized the title in their own quest for accreditation. As a result, we assume not only that The Gospel of Judas was not written by Judas -- after all, he had been dead for over a century -- but may not be what the public assumes a Gospel would be -- a collection of the stories and/or sayings of Jesus. For the four Gospels among the Nag Hammadi Codices have shown that the honorific title could be ascribed to works which we today would never call Gospels, if that title had not been attached to them in the tradition. The Gospel of Judas will in all probability teach us a lot more about the Gnosticism of the second century, than about the public ministry of Jesus, or sayings of Jesus, or Holy Week, or the like.

How has Judas been understood down through the centuries, after the New Testament presented him as giving Jesus over to the Jewish authorities, and The Gospel of Judas somehow vindicating him?

In antiquity, to fall on one’s sword when one’s leader is slain is considered a noble death. Should not Judas’ suicide after Jesus’ crucifixion be accorded this distinction of being a noble death? Apparently it was first Saint Augustine who decided that Judas’ suicide was in fact a sin.1 Listen to the way Augustine put it: 2

He did not deserve mercy; and that is why no light shone in his heart to make him hurry for pardon from the one he had betrayed.

And so, irrespective of what one might think of Judas giving Jesus over to the Jewish authorities, as implementing God’s plan of salvation, or as a traitor betraying his friend, he cannot be forgiven for his suicide!

The most generous that early Christian monasticism could be to Judas was to suggest that Jesus forgave him, but ordered him to purify himself with “spiritual exercises” in the desert, such as they themselves practiced.

In the seventh century, the Bible commentator Theophylact thought Judas had not expected things to turn bad once he arranged a hearing between Jesus and the Jewish authorities, and in anguish at the outcome killed himself to “get to Hades before Jesus and thus to implore and gain salvation”: 3

Some say that Judas, being covetous, supposed that he would make money by betraying Christ, and that Christ would not be killed but would escape from the Jews as many a time he had escaped. But when he saw him condemned, actually already condemned to death, he repented since the affair had turned out so differently from what he had expected. And so he hanged himself to get to Hades before Jesus and thus to implore and gain salvation. Know well, however, that he put his neck into the halter and hanged himself on a certain tree, but the tree bent down and he continued to live, since it was God’s will that he either be preserved for repentance or for public disgrace and shame. For they say that due to dropsy he could not pass where a wagon passed with ease; then he fell on his face and burst asunder, that is, was rent apart, as Luke says in the Acts.

A Dominican preacher, Vinzenz Ferrer, in a sermon in 1391, had a similar explanation for the suicide, that Judas’ “soul rushed to Christ on Calvary’s mount” to ask and receive forgiveness: 4

Judas who betrayed and sold the Master after the crucifixion was overwhelmed by a genuine and saving sense of remorse and tried with all his might to draw close to Christ in order to apologize for his betrayal and sale. But since Jesus was accompanied by such a large crowd of people on the way to the mount of Calvary, it was impossible for Judas to come to him and so he said to himself: Since I cannot get to the feet of the master, I will approach him in my spirit at least and humbly ask him for forgiveness. He actually did that and as he took the rope and hanged himself his soul rushed to Christ on Calvary’s mount, asked for forgiveness and received it fully from Christ, went up to heaven with him and so his soul enjoys salvation along with all elect.

Yet the all-too-rampant anti-Semitism of the Middle Ages exploited Judas as the arch-betrayer in order to arouse just such sentiments, by painting him as a caricature of a Jew, with exaggerated features, a large hooked nose, red hair, and of course greed for money. . .

1 A. J. Droge and J. D. Tabor, A Noble Death: Suicide and Martyrdom among Christians and Jews in Antiquity (SanFrancisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1992), cited by Klassen, Judas, 168 and 175.

2 Klassen, Judas, 47, quoting Augustine, City of God, 1.17 and Sermon 352.3.8 (Patrologia Latina, 39:1559-63).

3 The translation, by Morton S. Enslin, “How the Story Grew: Judas in Fact and Fiction,” in Festschrift in Honor of F. W. Ginrich, ed. E. H. Barth and R. Cocroft (Leiden: Brill, 1972), is quoted by Klassen, Judas, 173.

4 Quoted by Klassen, Judas, 7.

Copyright © 2006 James M. Robinson